Aesthetic experience is not so easily defined with precision.

We know that it often involves emotion, but it can’t be reduced to emotion without collapsing into something else—just an emotional experience. People sometimes describe it as transcendent, but it’s not identical to a religious experience, even if the two occasionally overlap.

This five-part series, sparked by someone recently asking about aesthetic experience, introduces philosopher Monroe Beardsley’s final and most complete account. He proposed five conditions: object-directedness, felt freedom, detached affect, active discovery, and wholeness. The first, object-directedness, is essential, and at least three of the remaining four must also be present for an experience to qualify as aesthetic.

Click to read about the first condition: object-directedness. If you’ve already read that one, then let’s talk about felt freedom.

What is Felt Freedom?

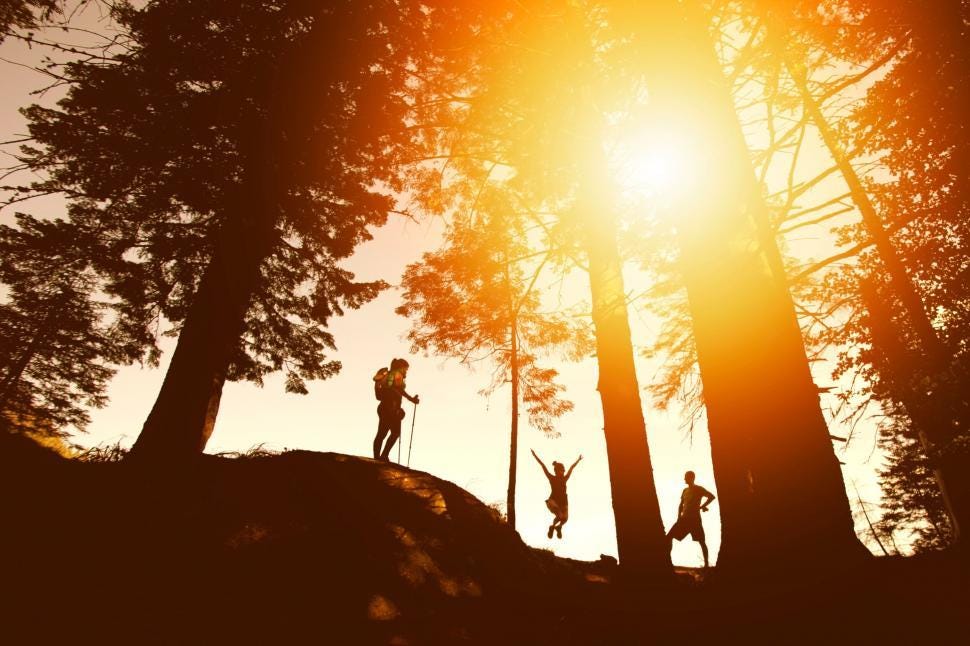

Imagine feeling anxious about a decision you have to make—perhaps you’re wrestling with whether to resign from a job and start something new. As you drive home, your thoughts race. Then you turn on the radio, and a captivating song fills the space around you. The eloquent vocals. The rhythmic thrum of bass and drums. The shimmering cascade of guitar notes. For a few minutes, your inner noise is quieted by the music. Your thoughts don’t disappear; they dissolve. You’re no longer evaluating, deciding, second-guessing. You’re simply in the music.

This, says Beardsley, is an example of felt freedom.

In his words:

“Felt freedom is perhaps the hardest feature to talk about very definitely.”

That’s why it may be more effective to point to moments like the one above, rather than trying to pin it down abstractly. Still, Beardsley offers this description:

“that lift of the spirit, sudden dropping away of thoughts and feelings that were problematic, that were obstacles to be overcome or hindrances of some kind.”

Some critics—often motivated by religious or political concerns—have feared that felt freedom is a kind of escapism, a way of avoiding the demands of real life. Beardsley acknowledges this concern. Felt freedom, after all, resembles the effects of certain recreational drugs, which can induce a similar sense of release.

But Beardsley insists that this kind of freedom is a genuine part of aesthetic experience. The fact that some people chase it artificially doesn’t invalidate the authenticity of the experience when it arises naturally in art or nature. Schopenhauer, the famously pessimistic philosopher, argued that art offers a much-needed respite from the suffering of life, a temporary release from the “will” and all its demands.

Extreme examples of felt freedom appear most vividly in moments of hardship. Primo Levi describes a powerful instance of this, brought on by reciting Dante’s poetry while imprisoned in Auschwitz. Yet we don’t need extraordinary suffering to recognize it. Think of how a breathtaking sunset after a long day, or a quiet moment in a gallery, can help you pause, breathe, and feel even slightly unburdened. Since Beardsley’s death in 1985, research in psychology and neuroscience has begun to confirm this connection. Experiencing art can lower cortisol and trigger a shift in mood, attention, even heart rate.

Conclusion

As discussed in Part 1, Beardsley considered object-directedness the only condition that must always be present. Of the other four, at least three are required. He likely excluded felt freedom as a necessary condition because not all art induces it. Some works confront us directly with injustice, grief, or confusion. They may be challenging or even distressing.

Still, when we find ourselves momentarily unburdened—when time feels suspended, and the chatter of the mind fades—we’ve likely entered felt freedom. That feeling of lifting, loosening, or floating just above the heaviness of ordinary life is a hallmark of aesthetic experience.

Look for Part 3 on “Detached Affect.”

*If you want to re-humanize your business, I can help! Let’s chat about collaborating: michaelrspicher@gmail.com

Relevant ARL Articles

Aesthetic Experience: A Basic Reason for Action

Performative Beauty and Knowledge by Connaturality

Review of The Experience of Beauty in the Middle Ages

ARL News

I’m biking 100 miles total throughout the month of June to help raise money for the American Heart Association. As someone with a heart condition, this has personal motivation for me. If you are able to donate, here’s the link.

I spoke with Emil Drud on Creative Odyssey about aesthetics, well-being, and business. Here’s a link to listen.

My latest article for BeautyMatter asks whether there are different stages of beauty throughout our lives.

Digital Fashion: Theory, Practice, Implications, edited by Michael R. Spicher, Sara Emilia Bernat, and Doris Domoszlai-Lantner, is available for purchase! (Our book was recently featured in a BeautyMatter article.)

Thank you for lifting up Beardsley! He’s always resonated with me, but now with neuroscience research in the picture, his explanation of the aesthetic experience seems even more apt and relevant.

That felt freedom really feels like touching the divine. It's why religion tries to claim domain over it, saying any other experience than the one they provide is infernal or sinful. At least, this is my opinion based on my experiences.