Recently, I was asked: What is an aesthetic experience?

Implied in this question is a deeper one—how does an aesthetic experience differ from other kinds of experiences, such as emotional or religious ones?

To explore this, I’ve decided to write a series of posts explaining philosopher Monroe Beardsley’s five conditions for aesthetic experience. After a long-running debate with fellow philosopher George Dickie (summarized here), Beardsley made one final effort to clarify his view before his death in 1985.

He identified five conditions: object-directedness, felt freedom, detached affect, active discovery, and wholeness. The first—object-directedness—is essential, and at least three of the remaining four must also be present for an experience to qualify as aesthetic.

One limitation of Beardsley’s approach is his narrow focus on art, often overlooking other places where aesthetic experience might arise. Still, these five conditions provide a useful starting point for a broader discussion, even if we ultimately decide he didn’t get everything right.

Object Directedness

This condition, according to Beardsley, is required for every aesthetic experience and is perhaps the most straightforward of the five. He explains it this way:

“I have in mind not only the plain and obvious cases where we are intensely absorbed in the contemplation of a painting or paying close and undivided attention to the course of the musical composition, but also other cases where the object or situation in question is merely intentional.”

The obvious cases include things like a museum painting or a live orchestral performance—clearly accepted as potential sources of aesthetic experience.

But Beardsley’s insight lies in extending this idea beyond traditional art objects, including even mental objects. Whether one reads a poem or recites it from memory, the effect on the listener—or oneself—can be equally powerful. Explaining intentional objects, he writes:

“we are concerned with what is happening in the world of a novel, we are thinking intensely and seriously of the symbolic significance of a figure in a painting, or, confronted with an instance of a conceptual or ‘idea’ art, we consider a proposition or a theme or a possible state of affairs the artist brings to our attention.”

Beardsley goes further. An aesthetic experience doesn’t just involve an object—it is directed at it. For example, a photograph might trigger memories of a ski trip, pulling us into nostalgia. That may be meaningful, but according to Beardsley, it’s not an aesthetic experience because our attention has drifted away from the object itself.

Aesthetic attention, by contrast, remains fixed on the object. We are absorbed in it, actively engaged with its form or meaning. It doesn’t merely point us somewhere else—it draws us in.

Conclusion

Beardsley devoted much of his career to refining this account of aesthetic experience, and his framework still offers a valuable foundation for contemporary conversations in philosophy, science, and culture.

We’ve started with the first condition: object-directedness. An aesthetic experience isn’t just a fleeting emotion or arbitrary response—it’s always an experience of something. That “something” could be a familiar object like a painting, a song, or a sunset. It could also be a mental construct, such as the imagined world evoked by a novel. Even a physical sensation, like a scent, might lead to a memory of a beautiful moment in nature.

But crucially, for Beardsley, there must be an object—some focus or anchor for the aesthetic experience.

Look for Part 2 on “Felt Freedom.”

*If you want to re-humanize your business, I can help! Let’s chat about collaborating: michaelrspicher@gmail.com

Relevant ARL Articles

Aesthetic Experience: A Basic Reason for Action

Performative Beauty and Knowledge by Connaturality

Review of The Experience of Beauty in the Middle Ages

ARL News

My latest article for BeautyMatter asks whether there are different stages of beauty throughout our lives.

I spoke with Jessica Quillin about luxury and aesthetic experiences on the Fashion Strategy Weekly podcast.

I spoke with Tony Martignetti on his podcast The Virtual Campfire. We talked about how aesthetics transforms our lives.

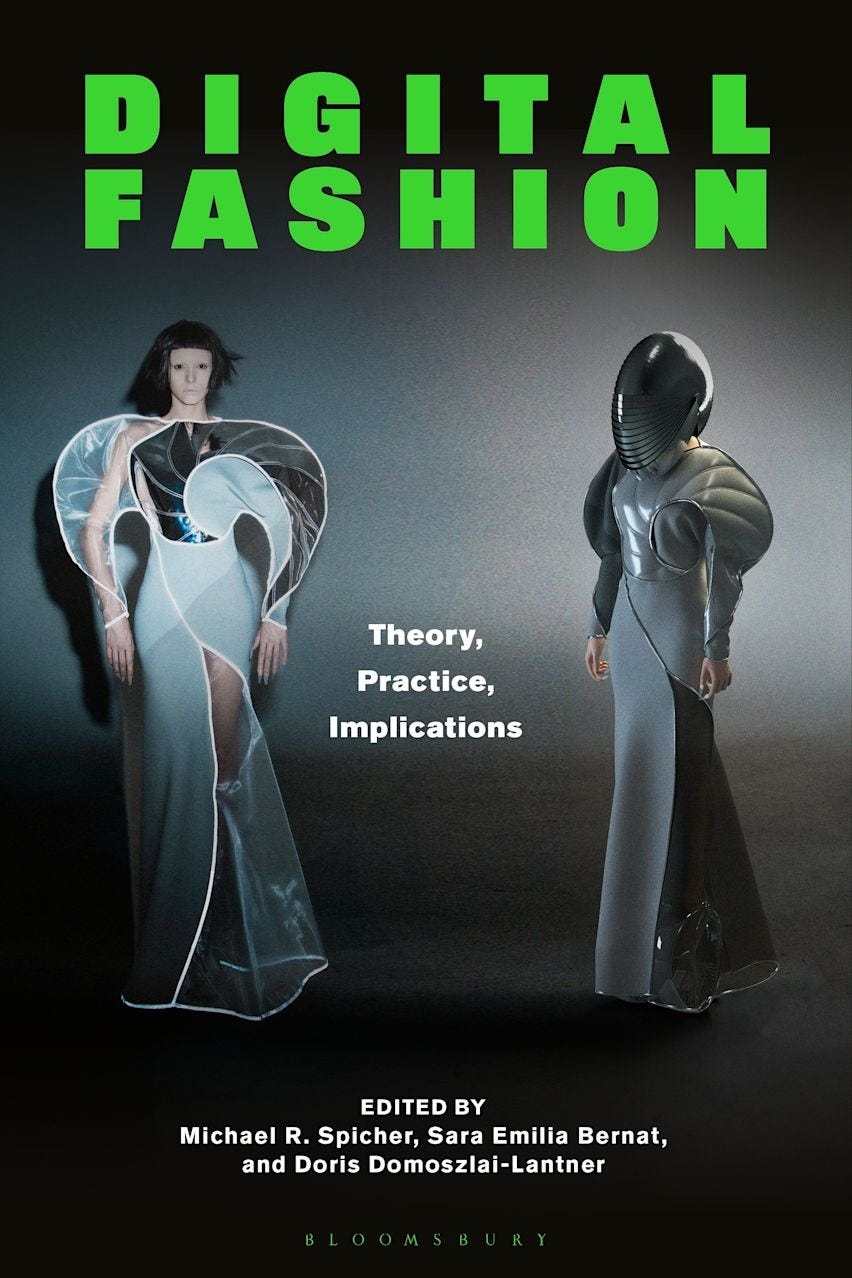

Digital Fashion: Theory, Practice, Implications, edited by Michael R. Spicher, Sara Emilia Bernat, and Doris Domoszlai-Lantner, is available for purchase! (Our book was recently featured in a BeautyMatter article.)