In her book, Thinking in Bets, former poker champion Annie Duke discusses how we achieve better objectivity in decision-making when we interact with those holding contrary opinions. For example, we might assume that the job of a judge is to find the truth in a particular situation in order to make a good ruling. She explains that Justice Powell intentionally hired liberal clerks because he acknowledged that he was more naturally led to the conservative viewpoint. He wanted these liberal-leaning clerks to challenge his thinking. Duke laments that the Supreme Court Justices since about 2005 have surrounded themselves with more likeminded clerks, creating their own echo chambers. This is not limited to political or legal contexts; this kind of echo chamber creation can pervade and adversely affect science and business.

In a previous article, I presented some thoughts about the beauty of teams. There, I focused on creating balance among the various people on the team. For example, a team of visionaries have great ideas but not maintain consistent follow through. Here, I want to home in on a particular kind of balance, which arises from allowing dissent.

I had a philosophy professor years ago who would begin each class by getting a sense of how we felt about the reading for that week, whether the majority tended to agree or not. Whichever position seemed to be the most prevalent among the students, he would defend the opposite position. The goal was to force us to hone our own arguments but also acknowledge some merits of the opposing position. In other words, it was to prevent us from dismissing a view too easily or overlooking any benefits of that view. When a group tends to agree on a particular point, they require less evidence to believe things that support their view.

Dissent is Vital to Objectivity

Philosophers have long debated about the nature of truth. Often, the answers are stretched on a continuum between objective or absolute truth and subjective truth. However, even the staunchest advocate for the objectivity of truth must acknowledge that, as finite human beings, we certainly do not grasp all truth infallibly. In other words, no one of us ever possesses the whole truth.

Contrast is an artistic term used to describe differences that help move the beholder’s eye (or other sense) throughout the work. There are some exceptions, such as some works of minimalism. However, if you stand in front of a painting and squint your eyes, you can frequently see contrast with light and dark areas, even as your squinting begins to blur the objects in the painting. If you squint and it all looks the same, then the painting has little contrast in terms of color. Now, color is only one aspect of art-making, so this may not be a problem for any one work of art. But sometimes it can show that there is little variety in an artist’s composition.

When you ‘squint’ at your team, what do you see? Are they a group that tends to think similarly to each other? Or are they anxious to present opposing views because they don’t feel dissenting opinions are welcome? Duke writes: “Diversity is the foundation of productive group decision-making, but we can’t underestimate how hard it is to maintain.” This idea hearkens back to the notion of uniformity amidst diversity, championed by Francis Hutcheson in his discussion about beauty. Too much uniformity is boring, ugly, and less likely to yield closeness to truth.

If you want a team that is beautiful and has a higher chance of truth, then you should value diversity. But this does not mean mere visual diversity. We should want a diversity of opinions and the psychological safety to comfortably express dissenting opinions. In her book, Duke explains we are biased beings. And we need direct challenge to escape from our tendency to accept a particular point of view.

Conclusion

As we think ahead to 2025, many of us will think about resolutions or other goals for the new year. Let’s challenge ourselves and our teams to seek out and encourage dissenting opinions. Obviously, we want to have reasonable and civl exchanges, but we should be more intentional about looking for opposing ways to see the world.

We know that each of leans more to one side or another on any given issue or idea. And if we surround ourselves with people that lean that way too, then we are likely to lean even more. This reminds me of how a guitar is constructed. Someone not familiar with the inner workings of a guitar is likely to see the strings and not worry about the pressure they exert on the neck of the guitar. However, guitars made of wood have a truss rod inside the neck to balance the force of the strings. Without this rod the strings would cause the neck to bend.

Poet John Keats wrote: “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty.” Diversity is a significant component of both. We need human truss rods to bring balance to our thinking and decision-making.

Holiday Special!!

20% off for a year subscription; click on the button below.

Relevant ARL Articles

Performative Beauty and Knowledge by Connaturality

Beauty and Truth in Scientific Research

ARL News

This fall has been productive! I’ve been interviewed on several podcasts which will air, starting in January. I gave talks about aesthetics to a wide array of audiences in business, architecture, and art. I’ve led workshops at businesses. Lastly, with my colleague Bella Zhang, I co-created and led a course called, “Aesthetic Paths to Flourishing.”

I have some availability for the spring, if you’re interested in having me speak or deliver a workshop. Email at michaelrspicher@gmail.com

My recent article for BeautyMatter explores aesthetic labor, click here to read it.

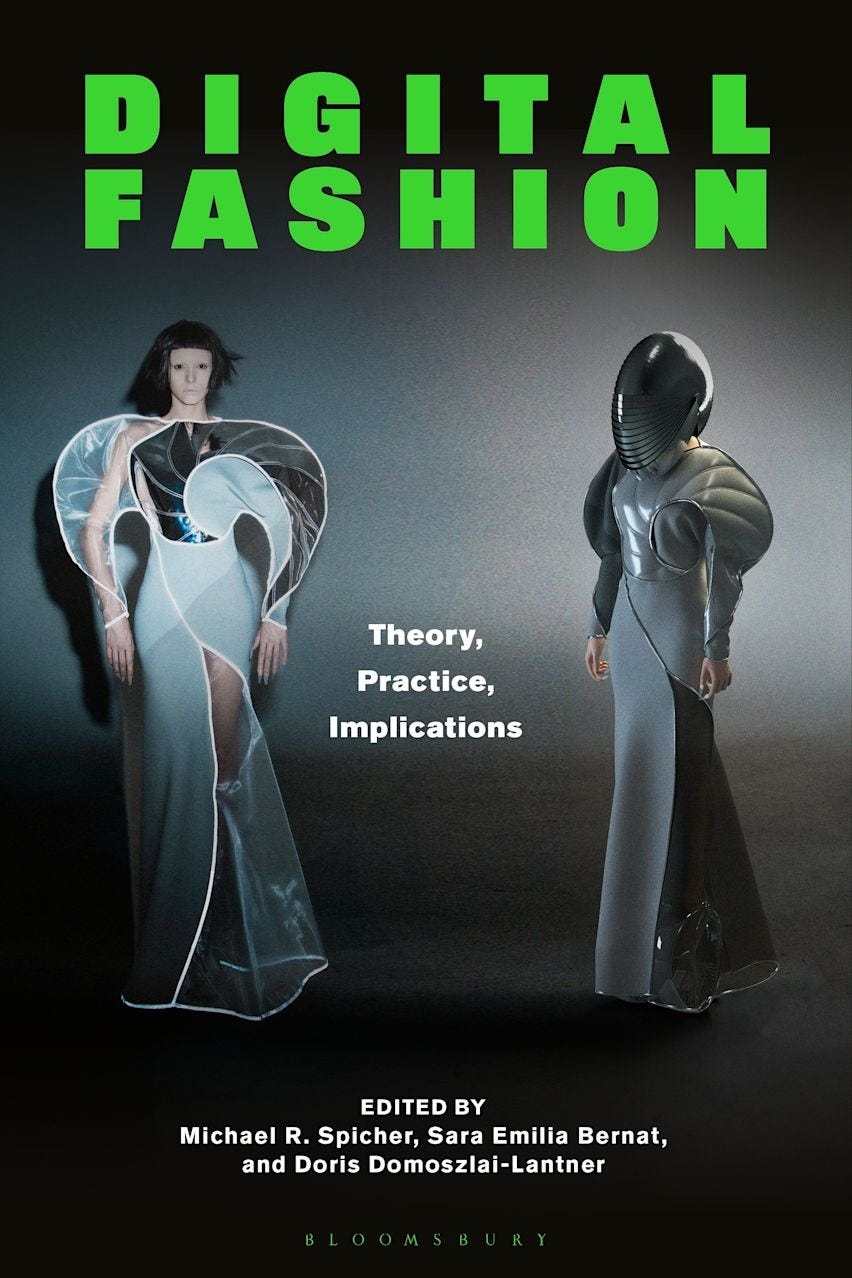

Digital Fashion: Theory, Practice, Implications, edited by Michael R. Spicher, Sara Emilia Bernat, and Doris Domoszlai-Lantner, is available for purchase!

Very interesting connection of beauty to truth!