The election cycle passed in the United States and elsewhere. We’ve heard many conversations, lectures, and commentaries about the same talking points, involving ethics, strategies, and the good of the nation. What we probably haven’t heard is anyone discuss aesthetics in these contexts. Two of the components of the political dimension of aesthetics are individuals developing their taste and communities using aesthetic taste terms to decry or praise other groups and issues.

Aesthetics and Personal Identity

When it comes to individuals, people identify strongly with their political, ethical, and religious beliefs. What this means is that if they were to change—such as moving from belief to atheism or conservative to liberal—most people agree that their identity has changed significantly.

An example comes from the 1956 film, Giant, starring James Dean, Elizabeth Taylor, and Rock Hudson. At the film’s start, Bick Benedict (played by Rock Hudson), a Texas ranch-owner, has overt racist attitudes toward Mexican Americans, some of whom work on his ranch. By the film’s end, he fights a man who made a derogatory remark at his daughter-in-law, who is of Mexican descent. On the other hand, Jett Rink (played by James Dean) begins the film as a carefree ranch-hand, who eventually strikes oil and gets wealthy. By the end of the film, he’s developed into a racist and a drunk. It’s clear from these two vignettes that both of these men underwent significant changes in their identities because of their ethical beliefs.

While ethical, religious, or political beliefs obviously affect one’s notion of self-identity, aesthetic taste may contribute as well. A team of four researchers sought to explore this hypothesis in their article, “The Aesthetic Self. The Importance of Aesthetic Taste in Music and Art for Our Perceived Identity.” Their conclusions require further research, but the initial findings confirm that the contours of people’s aesthetic taste form a central component of their identity. For example, people affirmed that changing from listening to only classical music to punk music would constitute a significant change.

Contrary to what we might think, our aesthetic taste and preferences shape our sense of identity. This explains in part why we get defensive if someone disparages a movie, band, or painting that we hold dear. It’s also why we should be vigilant and deliberate about our aesthetic choices, since they have such an influence on our identity. And while we may disagree with the preferences of others, we should understand that our aesthetic taste is influenced by our environments as well as by our decisions, just like them. This leads to the larger political context.

Aesthetics and the Political

“One surprising experience from ‘high politics’ is this: I have discovered that good taste is more useful here than a post-graduate degree in political science.”

-Václav Havel, former president of Czechoslovakia, wrote these words in his Summer Meditations (1991).

Aesthetics is rarely (by which I probably mean never) discussed in the context of politics. How does aesthetics appear in political contexts? Space permits me to discuss one key way: negative (and positive) aesthetic concepts and strategies.

The way we argue about issues ands people resorts to aesthetics regularly. As philosopher Per Bauhn notes, “Moral evaluations are couched in terms of judgments of taste – what is perceived as disgusting is taken as a manifestation of what is immoral.” Dictators and oppressors employ this tactic by connecting the “lesser” group of people with viscerally negative words and things, like disgusting, virus, rats, and so on. We further employ this strategy by calling entire groups of people criminals and terrorists. It leads to dehumanizing the other.

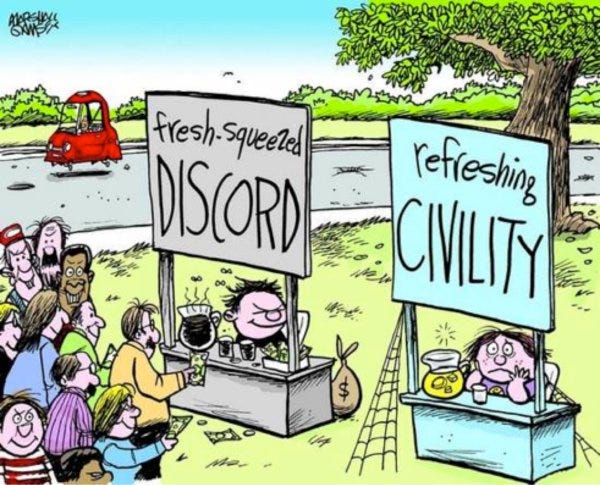

Inducing this visceral reaction proves far more powerful than appealing to any reasons when it comes to people’s views about others or issues. Now the aesthetics may not cause someone to change their mind on a given issue, but it helps push those supporters or near-supporters further into a frenzy concerning that issue.

People also employ this strategy to establish hierarchies, especially between the wealthy and poor. People with less money are often stigmatized as lazy, sloppy, and dirty. These terms appeal to our negative aesthetic responses that solidify an undesirable attitude toward people without as much. The wealthy do not escape from this process as we stigmatize them as tacky, vulgar, and arrogant. The goal is dividing people into us and them.

Many arguments about issues resort to feelings of disgust about the other person(s) because of their perspective. It’s not all negative; positive aesthetics can create feelings of patriotism as well. So, rather than ignoring aesthetic strategies in political discourse, we need to recognize its power and the parts we may inadvertently play in promoting these aesthetic tactics (in place of arguments and reason). For example, vegans and omnivores live together in (mostly) harmony, though they disagree with each other.

We want to believe that all our actions, decisions, and beliefs are made through a process of reasoning, but more often than not, our feelings guide us, and then we seek reasons for justification. If our aesthetic taste is intimately connected with our identity, then the more we employ negative aesthetics to dehumanize the other, the further we split the divisions between us.

What I’ve been up to.

I’m currently teaching a course at MassArt on Aesthetic Taste, where we’re discussing some theories, but also ideas in science, ethics, politics, and the future.

I’m writing monthly for BeautyMatter on the philosophical and scientific notions of beauty. So far, I’ve discussed origins of beauty standards, proportion, and integrity. I’m working on the next installment about radiance.

We’re at work editing our book on Digital Fashion for Bloomsbury Academic.

To invite me to speak or write to your group or organization, please email me at michaelrspicher@gmail.com

Relevant ARL Articles

Eating and the Tasteful Subject