The Overlooked Aesthetic of Touch

Historically and still today, people tend to prioritize seeing and hearing as the primary senses through which we experience the world aesthetically. These are often referred to as the “distance senses” because they allow us to perceive things from afar. A painting across the room or a symphony from a concert hall—these can be taken in without physically moving toward them.

By contrast, smelling, tasting, and touching require close proximity. While some scents can travel, taste and touch demand direct contact. And among them, touch is perhaps the most overlooked when thinking about aesthetics. Yet, it plays a profound role in our emotional, social, and aesthetic lives.

Touch and Human Well-being

Touch is far more than just physical contact. It’s fundamental to how we relate to the world and to each other. In fact, human touch is essential to well-being. Its absence can be damaging—emotionally, mentally, even physiologically.

Some formerly incarcerated individuals, particularly those who spent long periods in solitary confinement, have reported developing a hypersensitivity to human touch. What should be comforting becomes painful. Their nervous systems have adapted to touch deprivation, and its reintroduction is almost too much to bear. This hypersensitivity reveals just how much the human body and mind depend on touch. We don’t just desire it; we’re wired for it.

A poignant example of this comes from the 2017 film Oh Lucy!, which tells the story of a lonely, middle-aged woman in Tokyo who enrolls in an English class. The teacher, an American, takes a tactile, interactive approach to teaching, and he begins each session with a hug. At the first class, she’s hesitant. But by the second hug, she clings to him, seeking something deeper than a mere greeting. That brief physical interaction breaks through her isolation. For a moment, she transcends the dull weight of loneliness and reconnects with life through the power of human touch.

The Power of Touch in Everyday Aesthetics

In Oh Lucy!, the woman doesn’t just fall for her teacher, she falls for what he represents: connection, warmth, attention, presence. All of that is awakened by touch. And while we may not think of it as necessary like air or water, touch—especially meaningful, intentional touch—is critical to human flourishing.

But touch isn’t limited to human contact. It’s also fundamental to how we relate to objects.

Years ago, when I was buying my first bass guitar, an older salesperson gave me advice I’ve never forgotten: Don’t get caught up in brand names or hype. The only things that matter are how it sounds and how it feels. Both matter equally. A beautiful tone is important, but if it doesn’t feel good in your hands—if the neck is too wide or the finish too rough—you’ll never want to play it. That tactile relationship becomes a kind of dialogue between you and the instrument.

We often think of instruments as tools for producing sound. That’s true for the listener. But for the musician, the instrument is also a tactile companion. There's a kind of choreography in how fingers glide across strings or keys, in how weight is distributed, in how resistance and smoothness interplay. These are aesthetic experiences rooted in touch.

Touch in Design and Consumer Experience

Businesses are not blind to the importance of touch, either. Some of the most successful product designs are those that attend not only to how a product looks or functions but also to how it feels. Apple, for instance, is known for designing devices that feel good in your hand. The curvature of the iPhone, the resistance of a MacBook trackpad, the smoothness of the Apple Pencil; these are intentional aesthetic choices.

Ironically, because of the cost and fragility of these products, we often encase them in protectors and cases that mute the tactile experience. There’s a kind of trade-off between protection and touch. Some phone cases attempt to preserve a sense of tactility, but it’s not quite the same. Still, the fact that consumers notice when a phone or device “doesn’t feel right” is a testament to how deeply embedded touch is in our aesthetic judgment, even if we don’t always articulate it.

In a world dominated by screens and sound, touch may seem like a secondary sense. But it’s not. It connects us—to others, to objects, to the present moment—in intimate and irreplaceable ways. Touch is a powerful, often unspoken element of beauty. And like all forms of beauty, we feel its absence when it’s gone.

*If you want to re-humanize your business, I can help! Let’s chat about collaborating: michaelrspicher@gmail.com

Relevant ARL Articles

Aesthetic Experience: A Basic Reason for Action

Performative Beauty and Knowledge by Connaturality

Positive and Negative Aesthetics

ARL News

I’m biking 100 miles total throughout the month of June to help raise money for the American Heart Association. As someone with a heart condition, this has personal motivation for me. If you are able to donate, here’s the link.

I spoke with Emil Drud on Creative Odyssey about aesthetics, well-being, and business. Here’s a link to listen.

My latest article for BeautyMatter asks whether there are different stages of beauty throughout our lives.

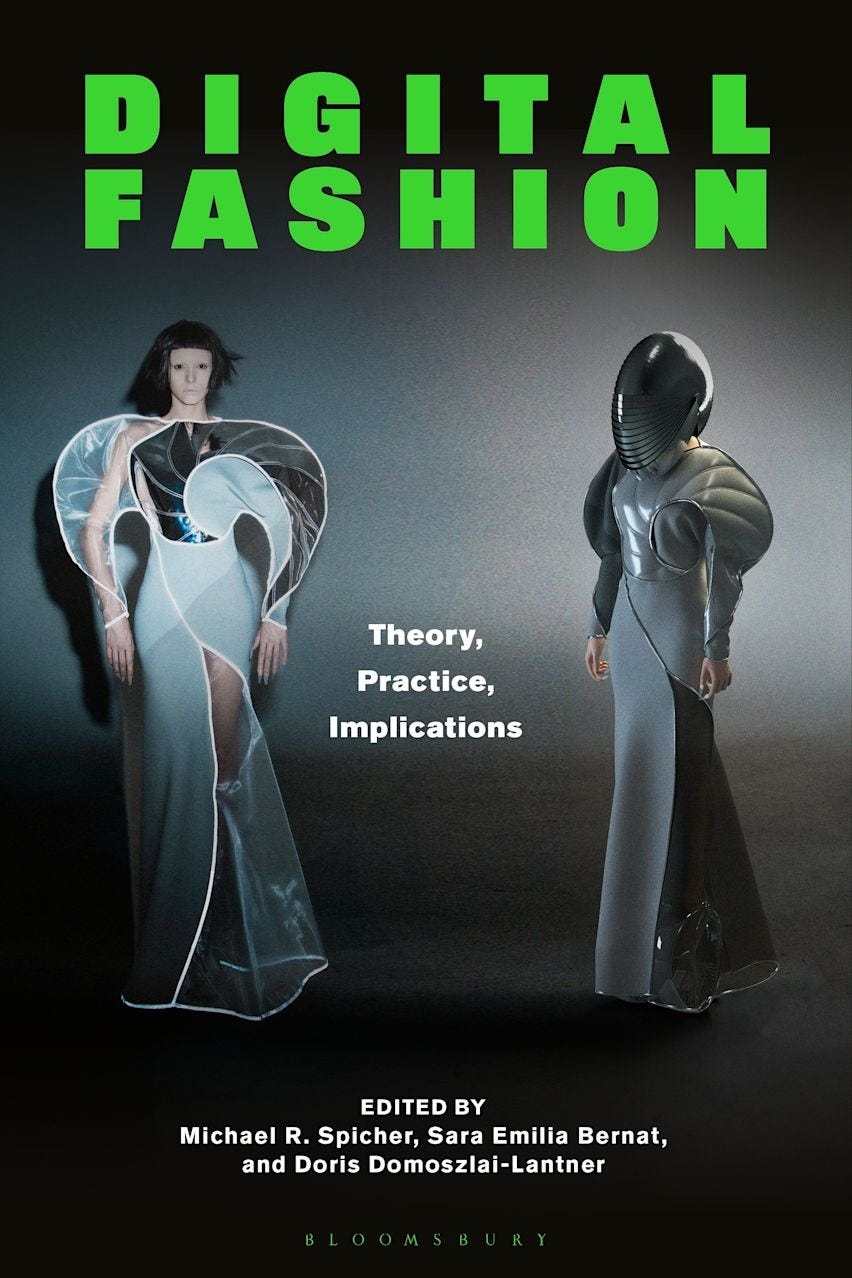

Digital Fashion: Theory, Practice, Implications, edited by Michael R. Spicher, Sara Emilia Bernat, and Doris Domoszlai-Lantner, is available for purchase! (Our book was recently featured in a BeautyMatter article.)

Great bit of insight and reminder here. It's making me wonder myself whether there is a priority in the senses, more than just a preference but an absolute priority. Perhaps our dissolution of touch in favor of (especially) sight is part of why we feel so disconnected from our world and ourselves.

I’m glad you explored this under-appreciated side of aesthetics. Very interesting!